Life expedition brings back first details on what is happening to the great liner on the ocean floor

Divers Explore The Sunken Andrea Doria

Kenneth MacLeish

|

| Kenneth MacLeish emerges exhausted from a dive to the Andrea Doria |

From time immemorial a ship lost in the deep sea has been a ship lost forever to the world's view. But modern diving and photography have changed that. The day (after the tragic sinking of the Andrea Doria on July 26 1956), two daring amateur divers, Peter Gimbel and Joseph Fox, reached the wreck and brought back black and white photographs. Since then LIFE has organized an expedition to get color photographs at the forbidding depth the Andrea Doria lies. LIFE Editor Kenneth MacLeish with Gimbel and three veteran divers from the West Coast went down to the wreck and took pictures. Here MacLeish describes what the diver-photographers found, saw and felt on their peril-laden assignment.

![]()

"If the sea were a woman," the diver said, "she'd be a bitch." The

lookout braced in the corner of the rolling bridge deck held his binoculars on the

haze-softened line of the horizon. In the waning sunlight the open sea 50 miles out of

Nantucket looked serene enough. But the sea had thwarted us for days and it did so still.

Now, for the first time in a week, a diver might challenge the offshore depths without

threat of wind or wave or darkened sky. He might make his way down to the huge hulk of the

sunken Andrea Doria and view her and be brought safely aboard again. He might, that is, if

we could find her. But the dead ship lay hidden 240 feet beneath the changeless seascape

through which we cruised. We found neither marker designating her grave nor any

manifestation from the deep to reveal her resting-place.

|

| Top:Robert Dill, Earl Murray Bottom: Ramsey Parks, Peter Gimbel |

Twice before we had set out to find the ship, only to be turned back by a battering

chop and fog-shrouded seas. Today, fair weather and pinpoint navigation had brought us to

her presumed position at the height of the sun and the slack of the tide, perfect

conditions for a dive. The divers-Bob Dill, Earl Murray and Ramsey Parks from the Coast,

Peter Gimbel from New York-climbed up to the flying bridge to look for the yellow oil drum

that had been set out by the Coast Guard at the time of the sinking. We looked, and laid

out our gear, and looked again.

The ocean's surface revealed that the lost liner was somewhere near: iridescent oil slicks

filmed the water in ragged patches; lumber and matting lured us to futile side excursions;

a blue shark, attracted by the debris, slit the water with a curving fin, and a great

humpbacked whale passed under our cruiser with a mighty swirl of his tremendous flukes.

But no yellow buoy appeared. We scouted methodically for six hours. Then, as evening came

on, we turned homeward. "Buoy must have carried away," said the Nantucket

navigator. "If it'd been there, we'd have found it".

The doctor joined us on deck. He was Lt. Commander James E. Stark, a young and dedicated

underwater specialist on leave from Navy. It was his job to help plan the dives and care

for any casualties. "If we ever do find her," he said, "we'll dive her

right. We don have to worry about these divers. None of them are heroes or tough guys or

glory hounds. That's good. But they won't get shook either They won't panic."

"Are you worried about the depth, Doc?"

"Let's say I wouldn't want it to be any deeper. Look: from about 150 feet down you

start getting more and more reaction from nitrogen in the compressed air you're breathing.

The deeper you go, the worse it gets. The nitrogen starts acting like an anesthetic and

begin getting nitrogen narcosis-the thing Cousteau calls 'rapture of the depths.' The

narcosis won't hurt you in itself, but it can reduce mental powers to those of a

staggering drunk.

"Matter of fact, there's an interesting parallel there. You can equate depth

tolerance with alcohol tolerance; the guy who gets blind on few very dry martinis may

become extremely dangerous to himself and his buddy at 150 feet; the guy who can drink six

without batting an eye can function-maybe-at 250. But one loses some resourcefulness past

150

"That same nitrogen in your blood produces the bends, unless you take precautions.

You're working down there at a pressure of six to eight atmospheres-that's six to eight

times the air pressure at the surface of the earth. When you come up, the gas in your body

can form little bubbles that can settle in your joints or spine or brain and cripple or

kill you.

"But the prevention is fairly simple. You wait just under the surface where there's

still pressure on you and allow the nitrogen to come out slowly without forming bubbles

inside your body. The length of time you decompress, and the depth at which you do it,

depend on how deep you've been, and for how long. I'll work that out for each dive.

"Then there's air embolism, the real killer: bubbles of air in the arteries. It can occur at any depth. It comes from not letting the expanding air out of your lungs fast enough as you come up. Near the surface, a change of only six feet of depth can rupture your lungs if you don't let the air out; and when the lung ruptures, air is forced into the blood. If it gets to the brain and blocks circulation you're a dead diver.

"But I don't think we have to worry."

The next day we left our cruiser in port and set out to search from the air. We flew a

course directly to the place where the Coast Guard marker should have been. Nothing.

But up ahead there was a strange configuration upon the calm surface a thousand feet below

us-a great spiral track, half a mile across, unwinding into a broad streak that

rode down the current to the horizon. It was oil. More important, it was oil from a fixed

and continuous source.

|

| Patches of oil bubbling up from the wreck gave the expedition the clue to its position. |

Surface oil, we knew, would simply drift along in a spreading, lengthening patch. But

oil from a fixed source would describe a curving tail across the moving water as the

turning tides reversed direction. The end of this trail, narrowing and thickening, would

always point to the leaking reservoir below. As we dropped to 200 feet and held our

glasses on the slick we, could see spheres of oil rising sluggishly through the clear

water to spread first into oval patches and then join together into a viscous stream

curving away down the ebbing tide.

There was no buoy, no wreckage, no froth, and no dim outline in the depths-nothing that a

ship searching the surface could have identified. But we knew that the Andrea Doria lay in

this place. The problem now was to determine where this place might be. By dead reckoning

and direction finder, we charted the wreck within a three-mile-square area. It took two

more days of search with the best of surface and subsurface electronic gear to pin down

our target. But finally the spot is marked. We are now ready to dive.

As the cruiser nears its destination the diver lays out his exposure suit and powders the slick rubber so that it will slip on easily. He is helped, and helps others, to get into the skin-tight garments.

"Ever had trouble with sharks?" someone asks Dill.

"Not often," he says. "Blues, like the one we saw back there, won't attack-not if they read the same books we do. Or unless we're one of those 'isolated incidents' they write about."

Each man readies his weight belt, knife, safety pack (an inflatable pod that can help him return to the surface), depth indicator and compass, facemask, swim fins and watch. Breathing tanks are rechecked for pressure.

Floor plans of the Doria are brought out and the divers huddle around them.

"We could just nip through these doors," says Dill, "and swim down this

hallway to the lounge doors. If we can open them, Earl and I will go in for a picture. But

that'll be 200 feet at least. Let's please remember which way to turn when we start

out."

"Remember now," says the doctor, "no more than 15 minutes down there. That

includes your descent time. Coming up, stop for 32 minutes 10 feet under the surface to

decompress if you've gone to 200 feet. Make it 6 minutes at 20 feet and 35 minutes at 10

feet if you go as deep as 225. Signal if you think you're going to run out of air while

you're decompressing and I'll bring you a fresh lung."

The diver sweats heavily in his airless rubber covering. He buckles on his accessories

and is helped into the heavy two-tank lung. He wets his mask and slips on his fins.

Mouthpiece in place, he waits for a signal. Then, with the three others, he falls backward

into the water, hands over face. He surfaces, joins his companions and works across the

strong current to the float marking the descent line, which will guide the divers down to

the wreck. This is a slender cord, which was dropped with an anchor from the cruiser when

the Doria was finally located.

The coolness of the water is pleasant to the diver's overheated body. The pale blue of the

undersurface is soothing to his eyes. Air flows easily into his lungs from the full

bottles on his back. When he raises his head to look about he senses his own minuteness in

an open ocean far from land. He looks down again, where the distances are at least

invisible. At the descent line he moves down to take his place -with the others who are

waiting a few feet under the waves. He sets his watch to an even hour, so that he will not

have to remember the odd minute of submergence, and clears, the trapped air from his suit.

The man deepest on the descent line gives the signal that all is well: each of the others

returns it. Then the procession moves swiftly downward.

Traveling headfirst, bare hands pulling and finned feet thrusting, the diver must gulp and

yawn and twist his jaw to allow the building pressure in his ears to equalize with the

pressure of air in his mouth and lungs. If he cannot clear his ears he must stop or even

retreat to shallower water until they adjust, otherwise his eardrums will burst.

At first he moves through a zone of pale water, warm to the touch, in which many

jellyfish drift. The light is almost that of day. But as he drives downward the light

fades swiftly. At 50 feet the water turns sharply colder. The fragile creatures of the

sunlit levels vanish. There is no more motion, no color but a deep blue-green.

It is at this level that the diver enters that peculiar realm which gives ocean diving its

most stirring quality-and, to some, its terror. Here there is neither surface nor bottom.

The earthling diver, accustomed to living in a place of planes and surfaces, becomes (as

Gimbel put it) "the center of a sphere bounded by the limits of his vision."

Free of gravity, he can move freely in three dimensions. Only the reassuring roughness of

the descent line in his hands and the graceful plumes of bubbles from the men below give

him spatial reference.

The metallic gasping of his air regulator echoes in his ears. The luminous dial of his

depth indicator reads 100 feet, then 130, then 150. The sound of his regulator grows

shrill under the mounting pressure and his air bubbles tinkle like small glass bells. His

watch shows him that he is 45 seconds down. And now his probing eyes sight a vague white

expanse. He leaves the descent line, angles down to the wreck and takes hold of her. His

depth indicator reads 185 feet, his watch, one minute past the hour. He does not yet feel

the narcosis, which he knows, will numb his mind but the chill of 48' water stings his

head and hands. The other men gather to exchange the all-well signal, then the group

divides.

The diver finds that he is holding onto a smooth, well-varnished rail. The grain of the

wood, the fresh paint of the metalwork, the neatly tied lacings of a canvas cover-all

these homely details are sharp and clear and disturbing before his eyes. He looks away

into the distance. The unmarred contours of the beautiful vessel stretch away for 60 feet

to the right and left, softening and at last vanishing in the blue-green shadowless

twilight. The ship seems immense, resembling a sunken city rather than a vehicle. She is

forbidding and austere. But she is also pathetic and full of a loneliness that chills the

diver's heart. ("She's not pretty anymore. It's sad to see her.") Her ports are

clean and unbroken, their brass rims bright, but they are dark and lifeless. Behind them,

in the glare of the diver's light, drowned curtains and mattresses and elegant furniture

float in strange suspension. Above all, the terrible incongruity of her situation strikes

the diver's senses. Perfect (to his eyes), unscarred, seemingly impregnable, still

equipped with every appurtenance of her impressive calling, this vast, intricate,

luxurious human habitation lies empty and abandoned outside the world of men. ("She

doesn't belong there. Your mind can't accept the sight of her, the way she is.")

Each diver feels these things and is awed and moved by them. Then he narrows his gaze

and his thoughts to the details, which he may study and photograph. He attempts small,

rational thoughts, and bends his attention to the simplest elements of survival.

The divers work in pairs, one man with a camera, the other, holding, a light and acting as

safety man. One pair moves up the side of the ship past several portholes. Only one is

open; from it a curtain waves in the current. They move on to a set of double doors

opening into a lounge. They enter the dark space. The narrow beam of the light picks up

details but reveals no general picture of the room. The water trapped inside is cloudy,

perhaps from the disturbance by the divers' fins and bubbles of the organic slime now

beginning to form on all surfaces. Lighter furniture has floated up against the door

through which they enter. Heavier objects have sunk to the far wall. There is great

disorder but little destruction. The men come upon an elevator shaft. Their depth

indicators show 200 feet. They are at the edge of safety. They look into the shaft. A

thundering crash (Perhaps the collapse of some sealed chamber) like that of a depth charge

echoes through the ship. They head back for the double doors but, as they swim through,

one of them gets hung up on a stainless steel coaming. (Later on, Murray explained

solemnly, "It was my sound training, scientific approach and good planning

that saw me through. I freed myself and swam coolly on." "Yeah," said his

partner, Parks. "Who was scared? You swam coolly on with two mahogany doors trailing

off you." "Okay," said Murray. "With all that booming, one six-inch

octopus would have scared me right out of the ship.")

The other pair works along the boat deck, where small striped fish hover around ports and

a tiny shark lies in a lifeboat. The current thrusts at the divers and they

have to hold on to keep in position. As their narcosis increase they cannot carry out all

the steps that have been planned. Tense, yet not fearful, they study and then restudy

their depth indicators straining to understand the perfectly legible but somehow cryptic

readings on which their lives depend. They swim a few strokes and recheck their watches

(The first 10 minutes go by so fast you can't get enough done," Dill said. "Then

during the last five you're so punchy and so worried about the time that you can't do much

more. And you get to thinking about things that could happen. Practical things, such as a

door closing or an air hose ripping, and fantastic things, like white hands reaching out

through a port to grab you.")

The divers swim to the wheelhouse and make their way inside. To do this they have to

unplug and clear away several emergency lighting cables that have blocked the doors. They

are proud of this simple achievement, which could have been carried out easily by a small

child at the surface. Outside, on the flying bridge, other divers are carefully examining

a big hooded searchlight. One of them is busily unscrewing with his bare fingers the large

bolt that holds it to its mount. It takes him a moment to realize that the bolt is not

turning and never will.

Within the wheelhouse the water has turned brown and dim. To the human eye the engine

telegraphs and other instruments are visible enough, gleaming in the dim light. But the

camera cannot record them; its brilliant flash illuminates every particle suspended in the

turgid atmosphere of the bridge, creating an impenetrable curtain of reflected light.

("Photography is pretty tough down there," said Murray. "Looking through

the finder takes a lot of concentration. Then, it's hard to take those floating flashbulbs

out of your bag and get them into the holder. When you finally do press the button, the

flash seems to come seconds late, like the explosion of an old flintlock musket. That's

how far apart your brain and fingers can get. And if a bulb collapses, the shock wave jars

you")

The men in the wheelhouse emerge at the same time and collide. One backs up and lets the other pass. Outside, in the tangle of cables, the lead man gets hung up. ("I wasn't worried," he insisted later. "I knew my buddy would come and get me out-sometime," he added, giving, his safety man a hard look. "What took you so long?")

Bob Dill travels alone along, the superstructure, moving first through the yawning

cabin class swimming pool, on to the ornate first class pool. Here he has reached

the midline of the ship. His indicator reads 220 feet. His face feels numb and thick. His

vision narrows. He is apprehensive but almost incapable of thought. ("I really had

the uglies, down there," he said.) He moves alone, the glass wall of the poolside

bar, searching in vain for doors before rejoining the others. He sees floating cushions

and furniture crowding in a great tangle against the glass.

The others have entered the glassed-in promenade deck and travel down it for a distance of

100 feet. Where people had once walked, they swim. Curtains are still tied back neatly

from the large windows. There is luggage stacked against the lower bulkhead, and shoes

("shoes all over the place-nice shoes") scattered along the way. A ring of keys

hangs in a lock.

|

| Robert Dill holds up a telephone recovered from the wreck |

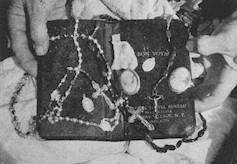

Far down the promenade they come upon an open window. Murray attempts to escape through this window and gets stuck. But the others, getting out through a larger window, come back and pull him out. Gimbel takes one small suitcase from the cluttered passage and carries it up to the surface. The other divers, motivated by some vague, numb-brain, inquisitiveness, bring up one odd shoe apiece. Then they rise quickly to 20 feet beneath the surface, make their way to the dangling anchor put down by the cruiser for them and hang there, shivering and exhausted. Finally they move up to 10 feet for the time prescribed by the doctor.

In the dim cabin, warmed by the throbbing diesels below, the divers sprawl on bunks and try to piece together the impressions they have gathered in three 15-minute dives of four men each. They are headed home, and will not return. They construct a picture of the ship as she lies at the sea bottom:

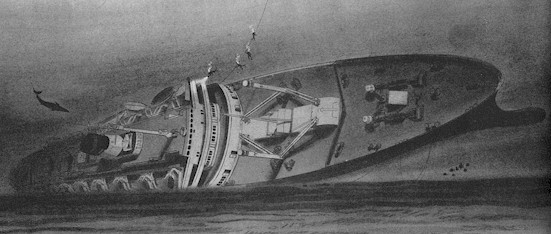

No one has seen the entire hull, since visibility is limited, but it can be determined that the wreck lies generally north and south, bow to the north. She had first lain almost completely on one side, but between Gimbel's first dive the day after the sinking and our present exploration she seems to have rolled about five degrees, perhaps because of the filling of the interior as trapped air escaped. Her decks stand now at about 85 degrees rather than 90 degrees from the level, sandy bottom. Air and oil still rise from her hatches, but in small quantities. At depth, the bubbles are compressed to small size; they expand as they rise. Oil floats from her in a small stream of pea-sized opalescent spheres. She seems, as Gimbel puts it, to be slowly in giving up her life.

|

| Life Magazine drawing based on the divers reports show how the Andrea Doria lies. The gash in the hull is on the side lying in the sand. |

The condition of her hull and outside fittings is startlingly good. Except for tangled lines and cables, and the disorderly disposition of her sunken lifeboats, she appears to be as well turned out as a cruise ship at dock. Her terrible wound is in her starboard side, now pressed into the sea floor; and there is no other sign of gross damage upon her. The thin film of slime, which is building up on her surfaces, particularly in enclosed places, is not apparent until a hand is brushed across her white paint, revealing a smudge of brighter white beneath.

In the small details of her exterior appointments there is still an unbelievable absence of sea change. Bright work still gleams, and the teakwood decks have not buckled or splintered. There is no flaking, blistering, peeling or rusting to be seen.

|

| A shoe in good shape, one of the hundreds abandoned by passengers taking to the boats, was brought up. |

Within the hull her normal appearance is eclipsed by violent disarray. The

accoutrements of lounges and saloons and staterooms which once stood unfastened

upon the carpeted floors now have risen (those that are lighter than water) to the upper

walls of the room, crowding in patternless confusion. Heavier objects have slipped to the

lower walls and lie in tumbled piles. Their colorings and coatings seem to have polluted

the water in which they are trapped, for within these spaces there is a brown, swirling

murk through which light travels with difficulty. Yet in the suspended turmoil of these

hidden spaces there are many objects which in themselves show no more effects of

submersion than simple wetness. There are documents and charts upon which ink is still

fresh and clear. There are delicate fabrics, which show neither stain nor tear. Shoes

retain form and color, and even their shine. Metal trinkets glitter as before. But deep

within the hull changes are taking place. Foodstuffs are starting to decay. Small

scavengers have crept in through the torn hull. In the ship's galley cans and jars have

collapsed under the water pressure and the corks of wine bottles have been forced inward.

As time passes, the sea will take over: wood, paper and cloth will deteriorate rapidly.

Paints and lacquers will soon disappear, though the cold clean waters of the north will

preserve them longer than would the warm tropic seas. Mineral deposits will encrust the

entire ship, but under them the metal, protected from oxygen, may last for

thousands of years. Silt will gradually fill the lower portions of the hull and, as

currents undercut the bottom beneath her, the ship will shift and settle deeper and deeper

into the ocean floor. In time the Andrea Doria will become a great lump, indistinguishable

from the sea bottom.

|

| Recovered suitcase contained rosaries, cameos and other souvenirs |

Their exploration ended, the divers' minds stay with the abandoned ship. They are obsessed with her dismal loneliness and her unexplored mysteries. "You come up," said one, "and you're glad to be up, and safe. But you can't get her out of your mind. You want to go back down right away, and stay longer, and see everything. Maybe it's a good thing we're done with her."